While reading selections from Edward Hirsch’s “Poet’s Choice” last week, I began thinking about which poems I would select if I were to write my own version. During this process I realized that I am not great at keeping a catalogue of the art that inspires and impacts me, and I’d like to use this space as an attempt to begin that catalogue. I have decided not to limit myself to poetry; I am a student of the visual arts as well as a student of art history, a music enthusiast, and so on, and I believe it is fruitful (and natural) to draw parallels between various artistic mediums. Thus, I will place each selection in conversation with a piece of activist literature. So, here it goes, my (abridged) Poet’s Choice:

Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass

Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass

Marcel Duchamp was a French artist (and naturalized American citizen), whose work has undoubtedly changed the course of art history. One of his most influential innovations is the concept of the readymade—an everyday (usually mass produced) object or compilation of such objects taken out of its original (read: practical, intuitive) function, sometimes modified slightly, and labeled as art.

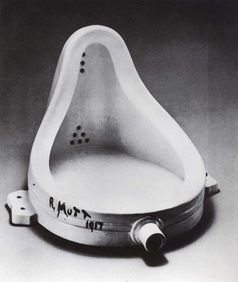

Duchamp’s most famous (or, at the time of its creation, infamous) readymade is entitled Fountain. To make this work, Duchamp simply signed a urinal R. Mutt—R. referring to the French slang for “moneybags” and Mutt referring to the manufacturer. Using this synonym, he submitted the work to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists.

Walt Whitman is often hailed as the “father of free verse.” He first gained attention as a poet when he self published Leaves of Grass in 1855. Whitman wrote sprawling, lyrical lines that seemed to go on forever and, when linked together, formed a new kind of epic. His free verse was unbounded, and truly “free.” The poems in Leaves of Grass also took up controversial themes, namely those of sexuality.

Both Duchamp’s readymades and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass challenged the standards of art at the time. Duchamp’s Fountain was rejected by the Society and widely criticized for being obscene, as was Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Both pieces attacked what was seen as the “proper” form of art making, threatening the validity of artistic institutions. However, both pieces were highly regarded by a handful of contemporary artists and are now held up as some of the finest works of their time. Duchamp’s readymades were (and still are) considered commentary on what art truly is, criticizing the artistic tradition and redirecting it in one stroke. Similarly, by essentially breaking all of the rules of poetry at once, Whitman created a new space for provocative poetry that did not have to follow conventions in form or in subject.

“Exile in Guyville” by Liz Phair and Lucille Clifton’s Poetry

Marcel Duchamp was a French artist (and naturalized American citizen), whose work has undoubtedly changed the course of art history. One of his most influential innovations is the concept of the readymade—an everyday (usually mass produced) object or compilation of such objects taken out of its original (read: practical, intuitive) function, sometimes modified slightly, and labeled as art.

Duchamp’s most famous (or, at the time of its creation, infamous) readymade is entitled Fountain. To make this work, Duchamp simply signed a urinal R. Mutt—R. referring to the French slang for “moneybags” and Mutt referring to the manufacturer. Using this synonym, he submitted the work to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists.

Walt Whitman is often hailed as the “father of free verse.” He first gained attention as a poet when he self published Leaves of Grass in 1855. Whitman wrote sprawling, lyrical lines that seemed to go on forever and, when linked together, formed a new kind of epic. His free verse was unbounded, and truly “free.” The poems in Leaves of Grass also took up controversial themes, namely those of sexuality.

Both Duchamp’s readymades and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass challenged the standards of art at the time. Duchamp’s Fountain was rejected by the Society and widely criticized for being obscene, as was Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Both pieces attacked what was seen as the “proper” form of art making, threatening the validity of artistic institutions. However, both pieces were highly regarded by a handful of contemporary artists and are now held up as some of the finest works of their time. Duchamp’s readymades were (and still are) considered commentary on what art truly is, criticizing the artistic tradition and redirecting it in one stroke. Similarly, by essentially breaking all of the rules of poetry at once, Whitman created a new space for provocative poetry that did not have to follow conventions in form or in subject.

“Exile in Guyville” by Liz Phair and Lucille Clifton’s Poetry

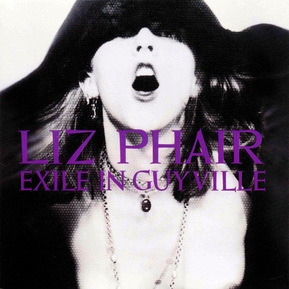

“Exile in Guyville” is the title of Liz Phair’s debut studio album from 1993. The 18-track album is a lot of things all at once—an indie rock record, a response to the Rolling Stones album “Exile on Main St.,” an exploration of what it is to be a young woman, vulnerable yet confrontational accounts of experiences real or imagined. The lyrics often reference romantic relationships, the entertainment industry, and sexuality.

One of the most striking songs on the album is entitled “Flower.” Like the album more broadly, the track is operating on several levels. It is a droning sexual monologue by a woman in an essentially reduced-to-robot state. She sings about how much she wants whomever she is addressing, yet exhibits essentially no enthusiasm with her tone. She mentions how infuriating she finds this person, yet she is filled with desire. Furthermore, her message has very dominant overtones (“I’ll fuck you till your dick is blue,” “I want to fuck you like a dog / I’ll take you home and make you like it,” etc.). I see this song as a sort of subversion of the male gaze, particularly in terms of women in the entertainment industry.

Lucille Clifton’s work likewise has many themes—sexuality, womanhood in the domestic realm, history/ancestry, race and race relations, to name a few—that function independently and in conjunction with one another. Her work is notably candid and no-frills, stripped of capitalization, complicated syntax, and the likes. Clifton, much like Phair, hides behind nothing.

Both Clifton’s poetry and Phair’s “Exile in Guyville” are markedly vulnerable—experiences and thoughts out in the open—without being confessional. They each speak of taboo subjects without trepidation (look, for example, at Clifton’s “wishes for sons” and Phair’s “Divorce Song”). Furthermore, each of them employs unusual images in their work (and for Phair this extends into her complicated guitar lines, which are sometimes so upbeat that they seem to contradict the lyrics, and at others so ambient they seem to at once envelope the song and melt into the background). Check out Clifton’s “cutting greens” for one of my favorite examples of her odd and compelling imagery, and give “Dance of the Seven Veils” (one of my favorite tracks on the album) for an example of Phair’s brilliant lyrics, full of strange images like “You can rent me by the hour / I know all about the ugly pilgrim thing / Entertainers bring May flowers.” Ultimately, these two artists’ work are required reading/listening because they subvert our expectations; it is not often that one encounters a woman chanting about her sexual prowess or speaking about death, violence, and segregation in regards to kale and collard greens. This art is smart, timeless yet of their times, and so refreshing.

“Artemisia and Susanna” by Mary D. Garrard and “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America or Something Like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley” by June Jordan

Mary D. Garrard’s “Artemisia and Susanna” is an essay in Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany that explores Artemisia Gentileschi’s Susanna and the Elders, a painting from 1610. It has long been assumed that the painter’s father, an accomplished painter himself, was the true author of this work, as Artemisia was only seventeen at the time of its completion (and because art historians have a habit of discrediting the achievements of non-male artists). The essay argues that Gentileschi did, in fact, paint this work, citing the way Susanna is depicted.

The scene Gentileschi portrays comes from a biblical story in the Book of Daniel. The story goes: two older men watch Susanna in her garden, then decide to accost her and demand that she have sex with them, or else they will say she was engaging in lascivious activity. She refuses, and is about to be put to death for promiscuity when the men are found out. It is intended to be a story about pious virtue (refusing the men) and justice (the men are found out). However, historically, the scene of so-called “seduction” was constantly selected for portrayal in painting. In these examples, the men are seen as daring and adventurous, while Susanna is overtly sexualized. Essentially, a horrific scene about rape becomes an opportunity to sexualize the victim of violence.

Gentileschi’s painting, however, does away with this tradition, showing the men as threatening and Susanna as repulsed, contorted away from the men in horror. She also does away with the lush garden scenery, which traditionally suggested eroticism. Gentileschi was a victim of rape herself, and the threat of sexual violence was constantly looming over her (via the unwanted advances of her father’s colleagues and her teachers).

June Jordan’s “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America or Something Like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley” is an essay that discusses the life and work of “the first Black human to be published in America.” Jordan speaks of Phillis Wheatley’s history as a slave for the Wheatley family, then goes on to examine her poetry in more depth. Jordan notes the racist phraseology Wheatley involuntarily assimilated from her education. Then, Jordan points to phrases, such as “intrinsic ardor,” that suggest Wheatley was covertly asserting her autonomy.

When her white sponsor (Mrs. Wheatley) died, she fell off the radar of the literary world. She experienced marriage, the death of three children, and wanted to publish a second volume of poetry. However, without white sponsorship, this never happened. We do not know about the pain and love Phillis Wheatley experienced; we do not know much about her life from her poetry, because the only poems that had the possibility of being published had to appease a society wrought with institutionalized racism.

I love these essays because they call into question the accepted view of great works by closely examining the specific context of their making. Gentileschi and Wheatley are both considered prodigious and genius, yet without the presence of white personal sponsorship (Gentileschi’s father and Wheatley’s owner) and institutional sponsorship (western canonization), their achievements are seen as invalid. Furthermore, each of these women created work specific to her personal experiences, and it is crucial to examine the context in which these works were made in order to understand historical bias. These biases permeate society, and they greatly effect how people view artworks today. Therefore, it is important to understand the lens through which art is presented, so that we might subvert that lens, and see the work for what it truly is.

—Mia Capobianco

RSS Feed

RSS Feed