I’ve always been interested in verbalizing the unsaid. We are living in a world where visual cues, design, pictures, and art control a chunk, if not all, thought processes and behavior patterns. We document memories by taking photos on a phone or camera, we entertain ourselves by watching visual shows, we study and make sense of concepts through diagrams, drawings, and presentations. For the average person, these simple activities don’t require a second thought; however, I have always been curious about how much people, society, the world is actually affected through these visual and graphic cues. It makes me wonder: what would the world be like without photos and art? How would we be able to tell the difference between specific concepts or ideas? Why do people tend to ignore the efforts of photographers and artists when it is so embedded in our lives? And most importantly, I become fascinated with how visuals might aid storytelling: What more can a single photo, diagram, drawing convey beyond the visual element? What is the background story behind it? Who is involved? What happened afterwards? Why did this happen? Why was it created? These pondering questions and thoughts have been with me ever since I could lift a pencil and draw pictures or write. I think as a Writing Seminars major, double minoring in visual arts and marketing/communications, I can’t help but try to process graphic cues (i.e. advertisements, fine art, photography, or even logos/typography) and attempt to uncover hidden meanings through imagery, streams of consciousness, and most importantly, poetry.

An interesting form of verbalizing graphic cues is actually “Photopoetry.” I became intrigued with this type of poetry after researching about ekphrastic poems and wondering: “If I can write poems for pieces of art—why not photographs, too?” In addition, I was taking a photography class this semester, so I was naturally inclined to weave some sort of connection between the two subjects that I was most passionate about—writing and art. After some research about photopoetry—or its various alternatives, “photopoeme, photometry, photoverse, photo-grafitti, etc”—I learned that it’s an art form to describe that the poem and photograph hold equal importance to each other and often are symbiotically related (Photo Pedagogy). Michael Nott, author of Photopoetry 1845-2015, a Critical History, says, “the relationship between poem and photograph has always been one of disruption and serendipity, appropriation and exchange, evocation and metaphor the relationship between poem and photograph has always been one of disruption and serendipity, appropriation and exchange, evocation and metaphor.” A brief historical analysis of the relationship between photographs and poems illustrate its emergence during the Victorian period. The term “photopoem” was first coined in Constance Philips’ Photopoems: A Group of Interpretations through Photographs (1936). The pairing between photographs and poems were relatively popular as both mediums were able to rely on each other for deeper meaning and storytelling. Even more, a blend of these two art forms become so coherent that it forces the viewer to enter a sort of “montage thinking”—montages of text and image draw our attention to the act of reading/thinking, thus the reader/viewer becomes a collaborator in the creation of meaning (Michael Nott, Photopoetry 1845-2015). Photopoetry also creates a new level of social engagement because viewers are not only participating in “montage thinking,” but the very act of taking photos of people or places involves communicating and “engaging” with society, per say. The moments, events, people captured in the photos at the specific time—one wonders what’s happening and who’s in the picture. And to be able to complement a poem with the very act of photography is a type of social engagement that I would say is underrated, yet could open doors to new styles of poetry, or even beyond the creative arts.

I don’t necessarily want this blog post to be a history lesson about photopoetry, but rather a discussion about my findings and new knowledge about an art form that I was unfamiliar with. In addition, I actually wanted to test out the actual form of photopoetry by giving it a go myself!

An interesting form of verbalizing graphic cues is actually “Photopoetry.” I became intrigued with this type of poetry after researching about ekphrastic poems and wondering: “If I can write poems for pieces of art—why not photographs, too?” In addition, I was taking a photography class this semester, so I was naturally inclined to weave some sort of connection between the two subjects that I was most passionate about—writing and art. After some research about photopoetry—or its various alternatives, “photopoeme, photometry, photoverse, photo-grafitti, etc”—I learned that it’s an art form to describe that the poem and photograph hold equal importance to each other and often are symbiotically related (Photo Pedagogy). Michael Nott, author of Photopoetry 1845-2015, a Critical History, says, “the relationship between poem and photograph has always been one of disruption and serendipity, appropriation and exchange, evocation and metaphor the relationship between poem and photograph has always been one of disruption and serendipity, appropriation and exchange, evocation and metaphor.” A brief historical analysis of the relationship between photographs and poems illustrate its emergence during the Victorian period. The term “photopoem” was first coined in Constance Philips’ Photopoems: A Group of Interpretations through Photographs (1936). The pairing between photographs and poems were relatively popular as both mediums were able to rely on each other for deeper meaning and storytelling. Even more, a blend of these two art forms become so coherent that it forces the viewer to enter a sort of “montage thinking”—montages of text and image draw our attention to the act of reading/thinking, thus the reader/viewer becomes a collaborator in the creation of meaning (Michael Nott, Photopoetry 1845-2015). Photopoetry also creates a new level of social engagement because viewers are not only participating in “montage thinking,” but the very act of taking photos of people or places involves communicating and “engaging” with society, per say. The moments, events, people captured in the photos at the specific time—one wonders what’s happening and who’s in the picture. And to be able to complement a poem with the very act of photography is a type of social engagement that I would say is underrated, yet could open doors to new styles of poetry, or even beyond the creative arts.

I don’t necessarily want this blog post to be a history lesson about photopoetry, but rather a discussion about my findings and new knowledge about an art form that I was unfamiliar with. In addition, I actually wanted to test out the actual form of photopoetry by giving it a go myself!

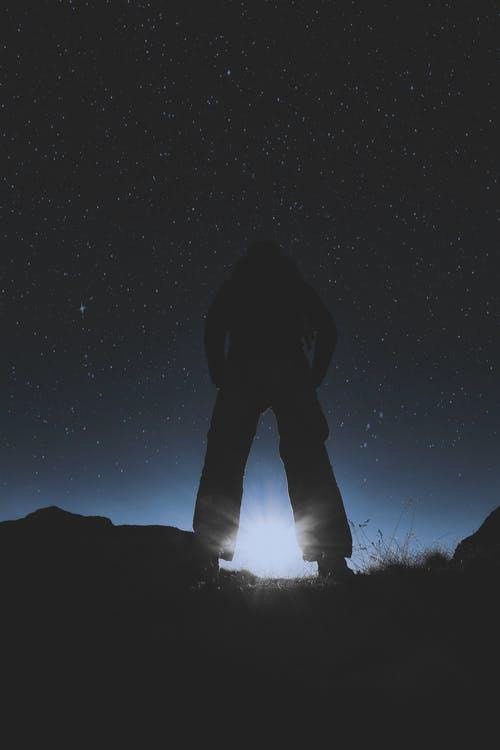

I came across this photograph while browsing for wallpaper backgrounds actually—but it immediately caught my attention because of the subject’s silhouette. I don’t know who the person is in the photo, but the angle of it definitely draws my eye to the sky, essentially doing the same action as the subject, or person—“looking up at the sky.” Along with the dark quality and heavy contrast of the black ground, silhouette, and the bright stars in the sky had me pondering—could there be something more that this photo could say? And I guess you could say those questions ended up leading me to this poem below:

TO LIVE

by Gina Kim

Cold, dark,

scary.

Drowning

In an endless black void

To abyss.

Tears that fill Niagara Falls,

Soundless screams echo as

I fall further down like I’m buried

Alive.

Cold, dark,

scary.

I fall like Niagara Falls

Until I hear a voice inside of me

“Open your eyes”

I look up

To see warm, bright, stars

Shining at me. Hope.

To live.

Overall, I thought the activity of actually trying to test out my research and findings was quite satisfying. I was able to put into action and actually create deeper meaning by aiding a photograph with a poem. It was a different experience for me as I was only able to do that for art pieces and drawings for ekphrastic poetry. Furthermore, engaging with poetry with photography was definitely a new level of If you haven’t yet tried to take a second thought and think about the hidden meaning behind your favorite work of art, or maybe an old photograph that you took and sort of forgot the reason why you took it, I would highly suggest sitting down for 20 minutes and just let your mind ponder, guide your thoughts, and write.

TO LIVE

by Gina Kim

Cold, dark,

scary.

Drowning

In an endless black void

To abyss.

Tears that fill Niagara Falls,

Soundless screams echo as

I fall further down like I’m buried

Alive.

Cold, dark,

scary.

I fall like Niagara Falls

Until I hear a voice inside of me

“Open your eyes”

I look up

To see warm, bright, stars

Shining at me. Hope.

To live.

Overall, I thought the activity of actually trying to test out my research and findings was quite satisfying. I was able to put into action and actually create deeper meaning by aiding a photograph with a poem. It was a different experience for me as I was only able to do that for art pieces and drawings for ekphrastic poetry. Furthermore, engaging with poetry with photography was definitely a new level of If you haven’t yet tried to take a second thought and think about the hidden meaning behind your favorite work of art, or maybe an old photograph that you took and sort of forgot the reason why you took it, I would highly suggest sitting down for 20 minutes and just let your mind ponder, guide your thoughts, and write.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed